Ancient Egyptian

Religious Influences on the Psalms of the Bible

By: David Deschesne

Editor/Publisher,

Fort Fairfield Journal, November 22, 2017

The modern literalistic interpretation of the Holy Bible presents the text as the ineffable, inerrant, holy word of God as dictated through man. However, what is lost on most students of the Bible is the context in which it was composed and what influences other religions of its day may have had on it. Intriguingly, some of the Psalms of the Bible’s Old Testament appear to exhibit an influence by its more ancient forbearer, the Egyptian religion.

Next to Hinduism, the religion of the ancient Egyptians is one of the oldest historical religions of mankind. Going back over 4,000 years, the Egyptian religion predates Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism and Taoism.

The ancient Egyptians named over 2,000 different gods. Some regions or cities of the country had their own specific gods. “At various times, the priests of Memphis, Heliopolis, Hermopolis and Thebes each claimed their city was the site of the Creation, and each ascribed the feat to its local god.”1

According to the Biblical account, the ancient Israelites, who ultimately composed the Old Testament of the Bible, were held captives as slaves in Egypt from around 1800 B.C. to around 1400 B.C.. However, it’s difficult to say with any degree of certainty the exact dates, or if the Exodus occurred at all, because “attempts to determine a comparatively accurate date for the Patriarchs are themselves doomed to failure, for in fact it is difficult to speak of the so-called ‘patriarchal period’ as a well-defined chronological entity, even where one accepted the biblical tradition as such.”2

According to the Bible, the Israelites were held captive in Egypt for around 430 years before being led out of bondage by Moses. While archeologists are still searching for evidence of this event, the ancient Israelites were certainly contemporary with those who practiced the religion of ancient Egypt. Consequently, they would have been familiar with many of Egypt’s religious icons, gods, traditions and hymns—traces of which ultimately became embedded in the Old and New Testaments and at least one of the Psalms, specifically, if not more.

King David began his reign around 990 B.C. He is credited with either composing or editing the Psalms into book form. While some of the Psalms are attributed to David’s pen, others are ascribed to Asaph; Solomon; Moses; the Ezrahites, Heman and Ethan; and other anonymous authors.3

While it’s impossible to accurately date the writing of each of the Psalms, some scholars have used context clues and cross references to other Biblical passages to come up with a well-educated approximation.

Most of the Psalms have been tentatively dated between 1060—1000 B.C. though some are much more recent, being dated around 500—400 B.C.4

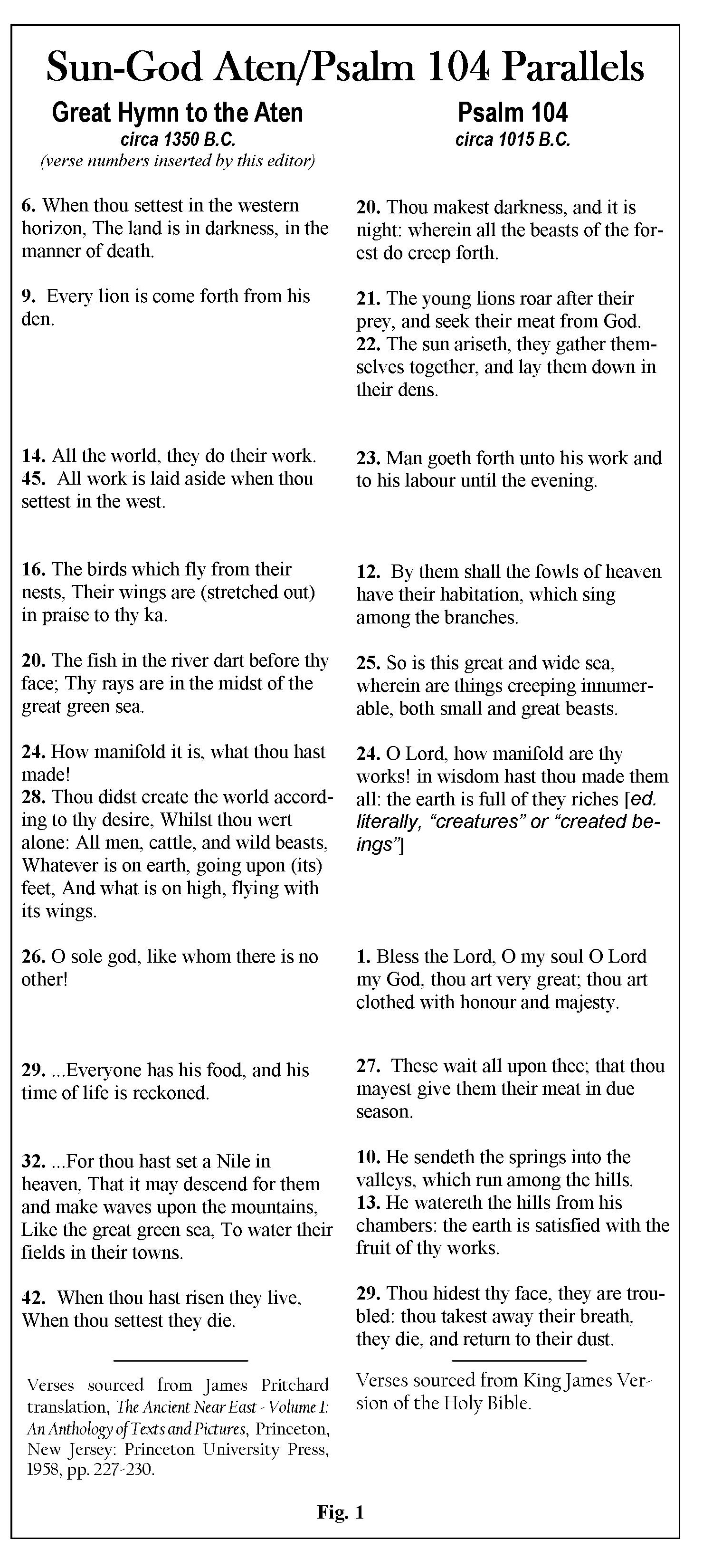

Psalm 104, which is estimated to have been written around 1015 B.C. and attributed to an anonymous author, appears to contain verses that are consistent with a hymn to an Egyptian god named Aten. The Great Hymn to the Aten was written over 300 years before Psalm 104 by the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep IV (later known as Akhenaten).

Amenhotep IV was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. He ruled for 17 years, during which time he changed his name to Akhenaten in order to glorify the god he believed to be the supreme god, the solar deity, Aten. He is most noted for abandoning the Egyptian’s polytheistic religion of many gods and attempting to establish a monotheistic (worship of one supreme god only) religion. Akehenaten tried to change his culture’s mindset and even established a new city called Akhetaten centered around the worship of Aten alone. After his death, his city and monotheistic religion were dismantled and lost to history until the 19th century, AD.

During his reign, Akenaten wrote a hymn to Aten showing is honor and worship. The Great Hymn to the Aten exists in a couple of different forms today and has been translated into English. Upon its translation, several intriguing similarities with Psalm 104, written over 300 years later, seem to be interpolated from the Great Hymn to the Aten. (see Figure 1 at the bottom of this page for an interlinear analysis. Keep in mind when reading about Aten, he was the Sun-god).

Psalm 23

The famous Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my Shepherd…”) is also said to have its origins in ancient Egyptian religious lore. While many sources online have said this Psalm is copied from a prayer or hymn to the Egyptian god, Osiris, none of them actually cite the hymn or its original text, which is pretty sloppy journalism. I have searched diligently and have still not found the alleged hymn that Psalm 23 was supposed to be copied from, but I have found the imagery of the ancient Egyptian religion, found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which could have been the inspiration for Psalm 23.

"The Book of the Dead," also called "The Book of Coming Forth by Day," was a book of funeral texts to be recited at a person’s death to help them to the underworld where they would be judged by Osiris. The underworld in the Egyptian religion was not “hell” as Christians consider it today. Rather, it was simply the place where the souls of the dead go to be judged.

The sun god, Ra (or Re) was said to go into the Dwat—the underworld— every night after setting in the West, traversing through twelve gates or stages before being reborn again the following morning in the East.

According to the Egyptian religion, the city of Abtu (now using the Greek form, Abydos) was the seat of worship of Osiris. Every day, the sun would end its course at Abydos and enter the Dwat through a gap in the mountains near the city.5 The mountain has a curious crescent shape surrounding the villages and in its centre is a gap (known as Pega-the-Gap) believed by ancient Egyptians to lead directly to the kingdom of the dead.6 It was believed the souls of the dead made their way to the other world by way of this Valley of Abtu which led through these mountains—also called the “Valley of Darkness” and the “Shadow of Death.”7 Once past that valley, the soul would enter the Fields of Peace (Field of Reeds in some texts. In Greek they were known as the Elysian Fields). Here, in the Fields of Peace, souls of the dead resumed their normal earthly activity such as eating, drinking and love-making within a paradise before moving on to be judged by Osiris. However, before fun and enjoyment, they first had to work to harvest the crops and do necessary construction work—just as in their life on Earth.8

While in the Fields of Peace, the souls would inhabit the appropriate level of status relative to the spiritual evolution they achieved while on Earth and were taught by enlightened souls until their entry into the Judgment Hall of Osiris. If their spiritual level was high enough they became one with the perfected souls, or returned to earth reincarnated as a spiritual master or sage to fulfill a specific purpose. All others were reincarnated up to five times on Earth in order to have more chances to grow and perfect their spiritual nature before becoming lost souls in the Dwat if they did not attain spiritual maturity.9

Psalm 23 opens with the statement, “The Lord is my Shepherd” and appears to be a veiled reference to Osiris, whose symbols are the shepherd’s staff and crook. Next, Psalm 23’s “green pastures” and “still waters” that are mentioned appear to reference the Fields of Peace of the Egyptian religion. The “Valley of the Shadow of Death” then corresponds with the Valley of Abtu between the two mountains where the sun-god, Ra ended his daily course, and through which all souls traversed to get to the underworld. The Psalm then ends lamenting on the fact that the writer will spend all the days of his life with the Lord.

While Psalm 23, as with many other passages in the Bible, is interpreted in a Judeo-Christian context, new research is showing many of those Old and New Testament narratives have their origin in the religion of ancient Egypt—rewritten and interpolated into today’s modern religious themes and motifs.

Notes

1. The Age of the God-Kings, ©1987 Time-Life Books, p.71

2. A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson, editor, ©1976 George Weidenfeld and Nicolsn Ltd., pp. 31-32.

3. The New Encyclopedia of Judaism, ©2002, Jerusalem Publishing House, p. 626.

4. www.blueletterbible.org/study/parallel/paral18.cfm

5. Egyptian Book of the Dead: Papyrus of Ani, E. Wallis Budge, p. cxxxiii

6. https://egyptsites.wordpress.com/

2009/02/12/abydos-desert-sites/

7. Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Mysteries of Amenta, Gerald Massey p. 64

8. The Age of the God-Kings, ©1987 Time/Life Books, p. 107.

9. The Book of the Dead: Hunnifer Papyrus, Dr. Ramses Seleem, p. 70.

Click on the image below to open a full resolution jpg for easier reading...